Introduction

Input tax credit on plant and machinery under GST continues to be one of the most contested areas under the GST regime, particularly where such machinery is installed using civil structures, foundations, or permanent supports. While GST was introduced with the objective of seamless credit, Section 17 of the CGST Act consciously carves out restrictive exclusions, especially in relation to immovable property and construction-related expenditure. This has led to recurring disputes on whether civil components that enable the functioning of machinery can themselves qualify for ITC.

Post-GST, taxpayers often rely on the traditional “functional test” evolved under pre-GST indirect tax laws to justify credit eligibility. However, the statutory framework under GST reflects a clear shift—from judicially evolved tests to legislatively defined boundaries. This article examines how ITC on plant and machinery must be evaluated strictly within the confines of Section 17(5) and its Explanation, identifies civil structures that remain ineligible, and analyses limited situations where integrated systems may still qualify. The focus is on statutory interpretation, judicial trends, and a compliance-first approach for taxpayers.

Statutory Framework Governing ITC on Plant & Machinery

The eligibility of ITC on plant and machinery is governed primarily by Section 17(5)(c) and Section 17(5)(d) of the CGST Act, read with the Explanation appended to Section 17. The Explanation provides an inclusive definition of “plant and machinery” but simultaneously excludes land, buildings, and other civil structures, as well as foundations and structural supports used for fixing plant or machinery.

This legislative design makes it clear that GST law does not permit a broad or purposive interpretation based solely on business use. Instead, ITC eligibility is subject to express statutory exclusions, regardless of the commercial necessity or functional utility of the asset. Therefore, any analysis of plant and machinery under GST must begin—and substantially end—with the text of Section 17 itself.

Statutory Primacy over Functional and Commercial Tests

A recurring argument advanced in GST disputes is that civil structures, foundations, or supports should qualify for input tax credit if they are functionally indispensable to the operation of plant and machinery. Such reasoning is typically drawn from pre-GST jurisprudence, where courts applied the “functional test” to determine whether an asset formed an integral part of manufacturing or service delivery.

However, under GST, the scope for such interpretative expansion is significantly curtailed. Section 17(5) operates as a statutory bar, and the Explanation to Section 17 expressly excludes buildings, civil structures, and foundations from the ambit of “plant and machinery.” Where the legislature has clearly demarcated eligible and ineligible assets, functional utility or commercial necessity cannot override the statutory text.

Courts have consistently held that in taxing statutes, equity, intent, or business expediency cannot be imported to dilute express exclusions. The GST framework reflects this principle by prioritising legislative clarity over judicially evolved tests. Consequently, once an item falls within an excluded category under Section 17, the enquiry must stop there. The functional test may explain why an asset is required for business, but it cannot, by itself, create ITC eligibility contrary to the statute.

Does the Functional Test Still Have Any Role Under GST?

The functional test, which examines whether an asset is essential or integral to business operations, has a long lineage under pre-GST laws such as central excise, service tax, and VAT. Taxpayers continue to rely on this doctrine to argue that foundations, supports, or embedded civil structures form an inseparable part of plant and machinery and should therefore qualify for input tax credit under GST.

However, as per our experience in GST audits and appellate proceedings, the functional test today operates in a much narrower and subordinate role. Under GST, the test can at best assist in characterising an asset within the statutory definition of plant and machinery, but it cannot be used to override an express exclusion contained in Section 17(5). Once an item is categorised as a building, civil structure, or foundation, the enquiry does not extend to its functional necessity.

In other words, the functional test under GST is not a tool for expanding ITC eligibility but merely an interpretative aid where the statute itself is silent. Courts and authorities have increasingly rejected arguments that rely solely on commercial or operational indispensability. As per our experience, excessive reliance on the functional test without first addressing the statutory bar is one of the most common weaknesses in ITC litigation involving plant and machinery.

What Qualifies — and What Does Not — as Plant & Machinery Under GST

The Explanation to Section 17 provides the starting point for determining what constitutes plant and machinery for GST ITC purposes. Broadly, machinery, apparatus, equipment, and tools used for making outward supplies qualify for credit, provided they are not specifically excluded. Typical examples include production machinery, processing equipment, generators, compressors, and material-handling equipment directly used in business operations.

At the same time, the Explanation categorically excludes land, buildings, civil structures, and foundations or structural supports used for fixing plant and machinery. As per our experience, disputes most often arise where taxpayers capitalise such civil components along with machinery in their fixed asset register and assume GST treatment will follow accounting classification. This assumption is misplaced.

Factory sheds, RCC platforms, concrete bases, administrative blocks, warehouses, internal roads, drainage systems, and permanent supporting structures continue to fall squarely within blocked credit under Section 17(5), even if they are essential for housing or operating machinery. The GST law draws a clear distinction between assets that enable business operations and assets that are plant and machinery. As per our experience, successful ITC positions are those that respect this statutory distinction rather than attempting to blur it through functional arguments.

Grey Areas: Foundations, Supports, and Integrated Systems

The most contentious disputes on ITC relating to plant and machinery arise in cases involving foundations, structural supports, and integrated industrial systems. While the Explanation to Section 17 expressly excludes foundations and structural supports, taxpayers often contend that certain civil components are inseparable from the machinery itself and cannot function independently.

As per our experience, authorities closely examine whether the civil structure performs an independent structural role or merely exists as a housing or support mechanism. Where the foundation is nothing more than a concrete base to stabilise machinery, credit is generally denied. However, disputes become nuanced in cases involving furnaces, chimneys, silos, reactors, pollution-control systems, or effluent treatment plants, where civil and mechanical components operate as a single integrated unit.

The critical factor is not permanence or immovability, but whether the civil portion can be distinctly identified and separated from the machinery. As per our experience in audit proceedings, credits are more defensible where the taxpayer can demonstrate that the civil component has no standalone utility and is custom-designed exclusively for the machinery. Nevertheless, such positions remain litigation-prone and require strong technical documentation.

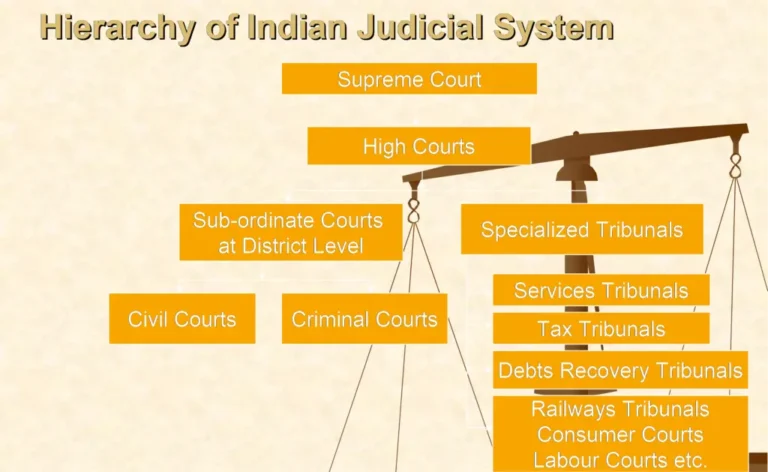

Judicial Approach Under GST

Judicial interpretation under GST has gradually moved towards reinforcing statutory discipline rather than reviving pre-GST doctrines. Courts and appellate authorities have repeatedly emphasised that Section 17(5) is a deliberate legislative restriction and must be applied strictly. Where the statute excludes civil structures and foundations, judicial sympathy based on business necessity has limited relevance.

As per our experience, recent rulings show a consistent pattern: credits are allowed only where the asset clearly falls within the statutory definition of plant and machinery and does not resemble a building or civil structure in substance. Authorities have been reluctant to accept broad functional arguments unless supported by precise statutory alignment.

Importantly, courts have also cautioned against mechanically importing pre-GST precedents without appreciating the changed legislative framework. GST is not a continuation of earlier indirect tax regimes but a fresh code with specific exclusions. As per our experience, taxpayers succeed where arguments are framed around statutory interpretation rather than commercial expediency. This judicial trend makes it imperative for businesses to reassess legacy assumptions on capital goods and ITC eligibility under GST.

Practical Classification Framework for Taxpayers

Given the restrictive nature of Section 17(5), taxpayers must adopt a disciplined and documentation-driven approach while evaluating ITC on plant and machinery. As per our experience, the most defensible positions are those where classification is undertaken before availing credit, not retrospectively during audit or litigation.

A practical framework would involve, first, identifying whether the asset is expressly excluded under the Explanation to Section 17, such as buildings, civil structures, or foundations. If excluded, the enquiry must ordinarily stop there. Second, where the asset is not explicitly excluded, taxpayers should assess whether it functions as machinery in its own right or merely supports another asset. Third, in integrated systems, technical drawings, supplier specifications, and installation contracts should clearly establish inseparability.

As per our experience, taxpayers often weaken their case by relying solely on fixed asset registers or accounting capitalisation. GST eligibility does not flow from accounting treatment. A contemporaneous classification note, supported by technical evidence, significantly improves audit outcomes and reduces litigation exposure.

Key Takeaways for Litigation and Audit Readiness

The GST law on plant and machinery reflects a conscious legislative choice to restrict ITC on civil construction, even where such construction is commercially indispensable. Functional or business-use arguments, while relevant for context, cannot override express statutory exclusions.

As per our experience, disputes escalate primarily where taxpayers attempt to stretch the definition of plant and machinery beyond the statutory text. A conservative, statute-aligned approach—particularly in respect of foundations and civil supports—often proves more sustainable in the long run. Courts have increasingly reinforced the primacy of Section 17 over equitable considerations.

Taxpayers should therefore reassess legacy assumptions carried forward from the pre-GST era and align ITC positions with the current legislative framework. Strong internal documentation, early classification, and restrained litigation strategies are key to managing risk in this area.

Points to Remember

- Input tax credit on plant and machinery under GST is governed strictly by Section 17(5) of the CGST Act and the Explanation thereto; business use or commercial necessity alone does not determine eligibility.

- Buildings, civil structures, and foundations or structural supports used for fixing plant and machinery remain expressly excluded from ITC, even if such structures are indispensable to operations.

- The functional test has only a limited and subordinate role under GST and cannot be used to override clear statutory exclusions.

- Accounting treatment or capitalisation of assets in the books does not decide ITC eligibility; GST classification must be evaluated independently.

- In cases of integrated systems, ITC positions are highly fact-specific and depend on whether civil components are inseparable and have no standalone utility.

- Pre-GST jurisprudence should be relied upon cautiously and only to the extent it does not conflict with the express language of Section 17.

- As per our experience, early classification, technical documentation, and conservative credit positions significantly reduce audit objections and litigation exposure.

- Attempts to stretch the definition of plant and machinery beyond the statute often weaken credibility during audit and appellate proceedings.

- A statute-first, compliance-oriented approach is more sustainable than aggressive interpretations based on equity or commercial expediency.

Related Reading

- Section 17(5)(d) — Meaning of “On Own Account” After Safari Retreats (SC)

(Understanding legislative intent behind ITC restrictions on immovable property and capital assets) - ITC on Immovable Property under GST: Post–Safari Retreats Landscape

(Analysis of what survives after the Supreme Court’s ruling and what does not) - Functional Test vs Statutory Bar in GST

(Why pre-GST jurisprudence cannot override express exclusions under GST) - GST ITC On Civil Structures: Section 17(5)(d) And Case Law

Sources and References

- Central Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017

Section 16, Section 17(5)(c), Section 17(5)(d) and the Explanation to Section 17 - Safari Retreats Pvt. Ltd. v. Chief Commissioner of CGST

Supreme Court ruling on ITC relating to construction and “on own account” - Supreme Court jurisprudence on strict interpretation of taxing statutes, including principles laid down in:

- Dilip Kumar & Co.

- CIT v. Kasturi & Sons Ltd.

Disclaimer

This article is intended for general informational purposes only and reflects a broad analysis of the statutory provisions and judicial developments under GST. It does not constitute legal or professional advice. The applicability of law depends on the specific facts and circumstances of each case, and readers are advised to seek appropriate professional guidance before taking any tax position.