Why ITC on Civil Structures Still Divides the GST World

GST was introduced with a clear promise — tax should not stick where business value is created. Input tax credit was meant to move smoothly through the supply chain. Yet, few provisions have disrupted that promise as persistently as the denial of ITC on civil structures.

Despite years of implementation, this issue continues to surface in audits, show cause notices, and litigation. Not because taxpayers misunderstand the law, but because the law itself sits uneasily with how businesses operate today. Civil structures are no longer just offices or premises. In many cases, they are directly used to generate taxable income — through leasing, infrastructure operations, or integrated commercial activity.

Section 17(5)(d) was meant to block credit on construction undertaken for self-consumption. Over time, however, its application has expanded far beyond that objective. What was intended as a narrow exclusion has become a routine ground for denial, often without examining how the structure is actually used.

Courts have responded by shifting the focus. Instead of asking whether a structure exists, they have asked what role it plays in the tax chain. That shift explains why similar fact patterns have produced different outcomes — and why the debate around ITC on civil structures remains unsettled.

This article looks at how that debate evolved, how courts have approached it, and why the answer to ITC eligibility in such cases is rarely straightforward.

Why ITC on Civil Structures Became a Problem under GST

From the outset, ITC on civil structures under GST was treated cautiously. Construction-related credits were excluded on the assumption that civil structures are long-term capital assets, not inputs consumed in making taxable supplies.

That assumption made sense in principle. In practice, it has struggled to keep pace with commercial reality.

Today, warehouses are leased, malls earn taxable rental income, and specialised facilities are built solely to support business operations. Yet, during audits, GST ITC on civil structures is often denied almost automatically once the construction is seen as resulting in immovable property. The enquiry frequently stops there.

This is why Section 17(5)(d) GST disputes arise even in routine business arrangements. Taxpayers who believe their claims are legitimate — particularly in leasing and infrastructure cases — find themselves defending credits that were never meant to be controversial.

The deeper issue lies in the overlap between property law concepts and GST credit principles. While property law focuses on ownership and permanence, GST is concerned with value addition and supply. What appears immovable under property law does not always function as a final consumer under GST.

This mismatch explains why ITC on construction of immovable property under GST continues to reach courts, and why outcomes differ from case to case. The law provides the restriction, but not clear answers for every commercial situation. Courts have had to bridge that gap through interpretation.

Understanding this background is essential. The next question — and the more difficult one — is how courts actually decide where the line is drawn.

What Section 17(5)(d) Allows — and What It Clearly Does Not

At the centre of the debate on ITC on civil structures under GST lies Section 17(5)(d) of the CGST Act. It is a blocking provision, drafted to deny input tax credit on goods and services used for construction of immovable property when such construction is meant for the taxpayer’s own use.

On paper, the restriction appears straightforward. In reality, it is anything but.

The legislative intent behind Section 17(5)(d) GST was to prevent credit on construction that results in assets meant for personal or internal consumption. Parliament consciously treated such construction as a terminal point in the tax chain. From a policy perspective, the law sought to draw a distinction between business inputs that flow into taxable supplies and capital expenditure that merely creates a space from which business is carried on.

However, the provision stops short of clearly explaining how this distinction should be applied in real commercial situations.

The law does not say that every civil structure is outside the credit chain. It does not say that every construction activity leads to automatic denial of GST ITC on immovable property. Instead, it introduces conditions — construction, immovable property, and use on own account — without defining how these conditions interact with modern business models.

This is where most disputes originate.

In practice, tax authorities often read Section 17(5)(d) as a blanket prohibition. Once it is established that construction has resulted in an immovable property, the denial of ITC on construction of civil structures is treated as a foregone conclusion. The enquiry rarely goes beyond the physical outcome of construction.

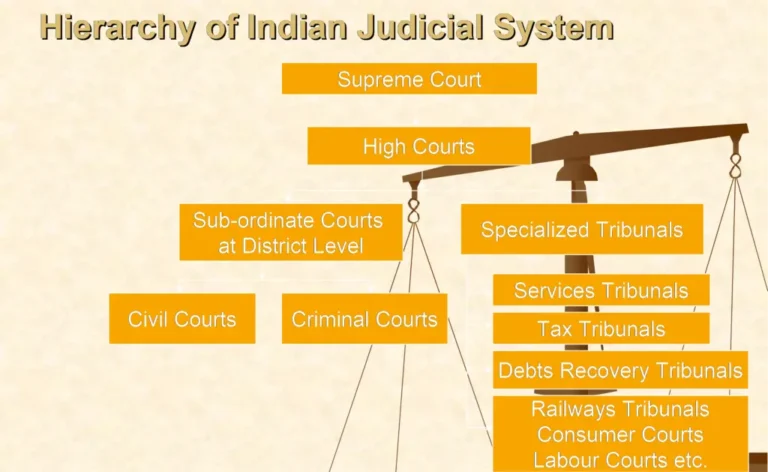

Courts, on the other hand, have taken a more careful view. They have repeatedly observed that Section 17(5)(d) cannot be applied in isolation. It must be read in the context of GST’s broader framework, which is built around the concept of supply, value addition, and avoidance of tax cascading. A provision that blocks credit must therefore be interpreted strictly, not expanded beyond its purpose.

This judicial approach has brought attention back to what Section 17(5)(d) actually seeks to prevent. It targets construction that ends in self-consumption. It does not automatically cover situations where the civil structure itself becomes part of a taxable arrangement, or where denying ITC under GST on civil construction distorts the credit chain.

From an experience standpoint, this is where many assessments go wrong. The focus shifts to the existence of a building rather than its economic role. The question becomes “what was constructed” instead of “how the output is taxed”.

For professionals and businesses dealing with GST blocked credit on civil structures, this distinction is critical. Section 17(5)(d) is not a simple yes-or-no provision. It is a restrictive clause that demands context, purpose, and factual analysis. Ignoring that nuance may simplify administration, but it does not reflect how the law has been read by courts.

The next logical step, therefore, is to understand how courts decide whether a structure is even immovable in the first place — because that classification often determines whether Section 17(5)(d) applies at all.

Immovable versus Movable Property: Where Courts Draw the Line

In disputes involving ITC on civil structures under GST, classification of property often becomes the turning point. Tax authorities tend to proceed on the assumption that once a structure is fixed to land, it automatically becomes immovable. Courts have consistently taken a more careful view.

In our view, this difference in approach explains why Section 17(5)(d) litigation has not settled despite repeated rulings.

Judicial pronouncements show that attachment to earth is not, by itself, decisive. Courts have examined the intention behind annexation, the degree of permanence, and whether the structure retains its commercial identity if dismantled. Where attachment is made only to ensure effective functioning or operational stability, courts have been reluctant to treat the structure as immovable in substance.

From a practitioner’s standpoint, this distinction is crucial for GST ITC on immovable property. Section 17(5)(d) applies only if construction results in immovable property. If, applying judicial tests, the outcome of construction is treated as movable, the blocking provision does not come into play at all. Denial of ITC on construction of civil structures in such cases rests on an incorrect starting assumption.

Based on judicial reading, courts have also cautioned against importing property law concepts into GST without adjustment. Tests developed for determining ownership or transfer under land laws cannot be applied mechanically to a tax built on value addition and supply. In our experience, this is where many assessment orders fall short — they rely on form and physical appearance rather than commercial reality.

In several rulings, courts have examined whether the structure can be relocated, whether it can be bought and sold as a unit, and whether its value lies in its function rather than the land beneath it. Where the answers point towards functional mobility, the conclusion that the structure is immovable becomes legally weak.

In our view, what emerges clearly is that immovability under GST is a question of fact, not assumption. Two structures that look identical may attract different ITC outcomes depending on why they were constructed and how they are used in the taxable chain.

For taxpayers dealing with GST blocked credit on civil structures, this analysis cannot be skipped. Classification is not a procedural step; it is a substantive legal exercise. Getting it wrong at this stage often determines the fate of the entire ITC claim.

Once courts conclude that a structure is immovable, the enquiry does not end. The next question — and often the most contested one — is whether such a structure can still fall within the plant and machinery exception. That is where judicial reasoning becomes even more nuanced.

Civil Structures and Plant & Machinery: Where Courts Slow Down Before Drawing the Line

Once a structure is treated as immovable, the debate does not automatically end. This is where the plant and machinery exception enters the discussion — and where courts have been most cautious.

In our view, this exception has been both overused and misunderstood in practice.

The GST law excludes land, buildings, and other civil structures from the definition of plant and machinery. At the same time, it recognises that plant and machinery includes apparatus, equipment, and machinery used for making outward supplies. The difficulty arises when civil structures are not independent constructions, but are inseparably linked to how plant and machinery function.

From a practitioner’s experience, tax authorities often treat this exclusion as conclusive. Once something is labelled a civil structure, the enquiry stops. Courts, however, have not adopted this short-cut.

Judicial reasoning shows that courts slow down at this stage and examine functional integration. They ask whether the structure merely provides a space for business, or whether it performs a role without which the machinery or system cannot operate. Where the structure exists only to support, stabilise, or enable machinery, courts have been willing to look beyond labels.

In our reading of judicial trends, courts have been careful not to convert every supporting structure into plant and machinery. Ordinary buildings, office blocks, and administrative spaces continue to remain outside the credit chain. However, where foundations, support frames, or specialised enclosures are designed exclusively for a specific operational purpose, the analysis changes.

This distinction is subtle but important for GST ITC on civil structures. A structure does not qualify merely because it is useful for business. It qualifies only when its existence is justified by the operation it supports, and not by the land on which it stands. Courts have repeatedly stressed this functional approach to avoid artificial expansion of the exception.

Based on experience, many ITC disputes fail at this stage because claims are framed too broadly. Taxpayers argue that the structure is “necessary for business”, while courts look for something more precise — whether the structure is indispensable for the machinery to function as intended.

In our view, the plant and machinery exception is not a tool to bypass Section 17(5)(d). It is a narrow carve-out meant for situations where denying credit would ignore how the business actually operates. When applied with restraint, courts have accepted it. When stretched, they have firmly pushed back.

This careful judicial approach explains why outcomes differ even when the facts appear similar. It also explains why the next and final layer of analysis lies not in definitions, but in how courts have applied these principles to real cases. That judicial pattern is what ultimately guides ITC outcomes on civil structures.

How Courts Have Read Section 17(5)(d): A Judicial Pattern Emerges

When disputes on ITC on civil structures under GST reach courts, the discussion rarely starts with denial. It starts with how the law should be read. Over time, a judicial pattern has emerged — not a single rule, but a consistent way of thinking.

In Bharti Airtel Limited v. Commissioner of Central Excise (2014, Supreme Court), the issue before the Court was whether telecom towers and related infrastructure, though fixed to earth, could be treated as immovable property for the purpose of denying credit under the then indirect tax regime. The Court held that mere attachment to earth is not conclusive, and that the correct test lies in examining the intention behind annexation, the degree of permanence, and whether the asset retains its commercial identity upon removal.

While GST law has since expressly excluded telecommunication towers from the definition of plant and machinery, rendering the outcome of the case inapplicable to telecom infrastructure under GST, the legal principle laid down by the Supreme Court continues to hold relevance. Courts have consistently relied on this reasoning to determine whether structures are immovable in substance, before applying Section 17(5)(d) of the CGST Act.

In our view, Bharti Airtel remains significant not for its conclusion, but for the method of analysis it introduced — shifting the focus from physical attachment to functional and commercial reality. That approach continues to inform judicial examination of GST ITC on immovable property, even where the statute ultimately blocks credit.

This line of reasoning was applied more directly in infrastructure cases. In Sterling and Wilson Private Limited v. State of Andhra Pradesh (2017, Andhra Pradesh High Court), the issue was whether a solar power generating system fixed to land could be treated as immovable property. The Court held that the system was attached to earth only for effective functioning and not for permanent enjoyment of land. Since the plant could be dismantled and relocated without losing its commercial identity, the Court treated it as movable in substance. From a practitioner’s standpoint, this case is important because it shows that courts are willing to look past physical fixation when examining GST blocked credit on civil structures.

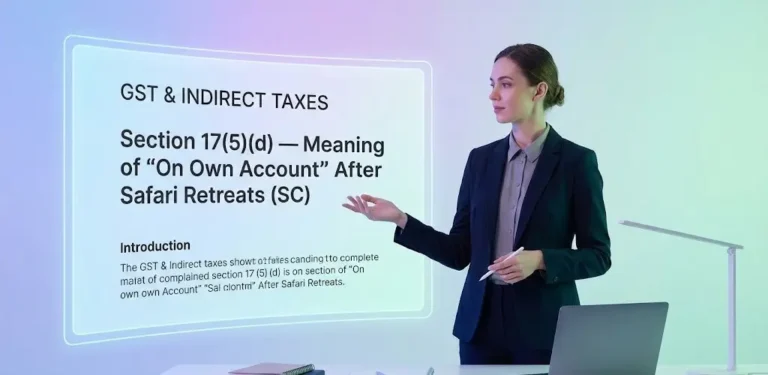

A different dimension emerged in leasing-related disputes. In Safari Retreats Private Limited v. Chief Commissioner of CGST (2019, Orissa High Court), the Court examined construction of a shopping mall intended for leasing. The Court observed that when a civil structure is used to make taxable outward supplies, denying ITC would lead to tax cascading, which goes against the very design of GST. On that reasoning, ITC was allowed. In our view, this judgment recognised that ownership alone cannot decide whether construction is “on own account” for the purpose of Section 17(5)(d).

However, When the matter reached the Supreme Court in Commissioner of Central Tax v. Safari Retreats Private Limited (2024), the Court set aside the Orissa High Court’s decision which had allowed ITC to avoid tax cascading. The Supreme Court held that Section 17(5)(d) expressly restricts ITC on goods and services used for construction of immovable property on the taxpayer’s own account, and that this restriction is a conscious legislative choice. The Court ruled that courts cannot dilute this statutory bar merely because the outcome appears harsh. Accordingly, the High Court’s approach was rejected and ITC was denied, with the Court observing that any relief must come from legislative amendment, not judicial interpretation.

Advance rulings have also contributed to shaping the debate. In Shibaura Machine India Private Limited (2022, Tamil Nadu AAR), the authority examined whether civil foundations and supporting structures essential for machinery operation could be treated separately from the machinery. It held that where such structures are indispensable for the functioning of plant and machinery, they form part of it, and ITC cannot be denied merely because they are civil in nature. From experience, this ruling reflects a pragmatic approach to GST ITC on civil construction, though its persuasive value depends heavily on facts.

In our view, these rulings reveal a clear judicial pattern. Courts do not treat Section 17(5)(d) as an automatic disallowance provision. At the same time, they do not permit credit merely to achieve tax neutrality. The outcome depends on how convincingly facts align with legal principles — intention, functionality, and economic role.

This explains why similar-looking structures attract different outcomes. The law remains the same, but the factual narrative changes. For professionals handling ITC on civil structures under GST, understanding this judicial pattern is more important than relying on any single judgment.

That judicial discipline ultimately shapes where the law leaves taxpayers today — a position that demands caution, documentation, and clear alignment with judicial logic.

Where This Leaves Taxpayers and Professionals Today

After years of litigation, one thing is clear — ITC on civil structures under GST is no longer a purely legal question. It is a mixed question of law and fact, and courts have been consistent on that point.

In our view, the mistake often lies in treating Section 17(5)(d) as either an absolute bar or a provision that can be worked around with aggressive interpretation. Judicial pronouncements show that neither approach survives scrutiny. Courts have repeatedly looked for a clear factual narrative explaining why credit is claimed and how the civil structure fits into the taxable supply chain.

From professional experience, disputes tend to fail not because the law is entirely against the taxpayer, but because the claim is framed loosely. Describing a structure as “used for business” is rarely sufficient. Courts look for a tighter explanation — how the structure contributes to taxable output, whether it performs a functional role, and whether denying ITC would distort the GST credit mechanism.

At the same time, recent judgments also serve as a reminder that courts will not rewrite the statute. Even where denial of GST ITC on civil structures leads to tax cascading, courts have shown restraint when the legislative intent is clear. This reinforces the need for caution. Not every commercial hardship can be cured through interpretation.

In our view, what Section 17(5)(d) ultimately demands is discipline — in structuring transactions, in documenting intent, and in presenting facts. The stronger the functional link between the structure and taxable supplies, the stronger the ITC position. Where that link is weak or indirect, litigation risk increases sharply.

For professionals advising on GST blocked credit on civil structures, this means moving beyond binary answers. The question is no longer whether ITC is allowed or disallowed in principle, but whether the facts of a particular case can withstand judicial examination. That assessment must be made before credit is taken, not after a notice is issued.

Until legislative clarity emerges, disputes under Section 17(5)(d) are unlikely to disappear. Courts will continue to decide them case by case, guided by purpose, functionality, and economic reality. For taxpayers and professionals alike, understanding that judicial approach is now as important as understanding the provision itself.

Conclusion: A Provision That Demands Judgement, Not Assumptions

In our view, the debate around ITC on civil structures under GST has survived this long because Section 17(5)(d) was never designed to operate in isolation. It was drafted as a restriction, but one that assumes careful application to facts, not mechanical denial.

Judicial decisions have made one position clear. The law does not permit credit simply because a structure supports business, nor does it justify denial merely because the structure is fixed to land. Courts have consistently examined how the structure functions, why it was created, and whether it genuinely sits at the end of the GST value chain.

For taxpayers and professionals dealing with GST ITC on immovable property, the lesson is straightforward. Eligibility is no longer decided by labels such as “building” or “civil construction”, but by the factual narrative that links the structure to taxable supplies. Where that narrative is strong and supported by evidence, courts have shown willingness to intervene. Where it is weak, even genuine commercial hardship has not been enough.

Until legislative clarity emerges, Section 17(5)(d) GST litigation will remain fact-driven and judgment-heavy. In that environment, professional discipline — in analysis, documentation, and presentation — matters as much as legal knowledge.

You May Also Like

Sources and References

- Bharti Airtel Limited v. Commissioner of Central Excise (2014) — Supreme Court

(Judgment available on the official website of the Supreme Court of India) - Commissioner of Central Tax v. Safari Retreats Private Limited (2024) — Supreme Court

(Judgment available on the official website of the Supreme Court of India) - Sterling and Wilson Private Limited v. State of Andhra Pradesh (2017) — Andhra Pradesh High Court

- Safari Retreats Private Limited v. Chief Commissioner of CGST (2019) — Orissa High Court

- Shibaura Machine India Private Limited (2022) — Tamil Nadu Authority for Advance Ruling

- Section 17(5)(d), Central Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017