Can Businesses Still Claim GST Credit on Buildings? The Real Impact of Safari Retreats Explained

Input Tax Credit (ITC) is the backbone of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) framework. The GST law is designed as a value-added tax system where tax paid on inputs is ordinarily available as credit against tax on outward supplies. However, ITC on immovable property under GST has always been an exception to this principle.

One of the most debated questions since the introduction of GST has been whether businesses can claim GST input tax credit on construction of buildings, especially when such buildings are used for commercial purposes like leasing, renting, or operating business establishments. This debate became sharper after several taxpayers argued that denial of ITC breaks the GST credit chain where outward supplies are taxable.

The controversy reached the Supreme Court in the case of Safari Retreats, where the taxpayer claimed ITC on construction of a commercial mall used for taxable rental income. The judgment delivered by the Supreme Court has now become a turning point in the interpretation of Section 17(5) of the CGST Act, particularly in relation to ITC on immovable property.

Post Safari Retreats, a common question faced by businesses, tax professionals, and students is:

Is input tax credit on construction of immovable property completely blocked under GST, or does any scope still survive after the Supreme Court ruling?

This article focuses only on that limited but crucial issue. It does not examine the constitutional validity of Section 17(5), nor does it engage in policy criticism or future legislative possibilities. Instead, it aims to explain, in clear legal terms, what the law practically allows and what it clearly prohibits after the Supreme Court’s decision.

By analysing the statutory framework and the Supreme Court’s reasoning, this article seeks to provide clarity on:

- Whether ITC on buildings used for business can still be examined, and

- How taxpayers should approach compliance and risk assessment after Safari Retreats.

Background – ITC Restriction on Immovable Property under GST

Under the GST regime, the entitlement to input tax credit is governed primarily by Section 16 of the CGST Act, 2017, which allows a registered person to take credit of tax charged on supplies used or intended to be used in the course or furtherance of business. However, this general entitlement is subject to specific statutory restrictions contained in Section 17.

Statutory Position under Section 17(5)

Section 17(5) of the CGST Act expressly lists certain categories of blocked credits, notwithstanding anything contained in Section 16(1). Among these, clauses (c) and (d) deal specifically with construction of immovable property.

In simple terms, the law provides that ITC shall not be available in respect of:

- Works contract services supplied for construction of an immovable property (other than plant and machinery), except where such works contract service is an input service for further supply of works contract service; and

- Goods or services or both received for construction of an immovable property (other than plant and machinery) on the registered person’s own account, even when such property is used in the course or furtherance of business.

This restriction is clear, unambiguous, and forms part of the original GST legislation enacted in 2017.

Meaning of “Construction” under GST Law

For the purpose of Section 17(5), the Explanation to the provision clarifies that the term “construction” includes reconstruction, renovation, additions, or alterations to the extent such expenditure is capitalised to the immovable property.

This clarification is important because it establishes that:

- Routine repairs and maintenance, which are not capitalised, do not fall within the blocked credit provision; and

- The restriction is closely linked to capital formation, not mere operational expenditure.

This position is consistently reflected in departmental clarifications and audit practice under GST.

Why Immovable Property Has Always Been a Blocked-Credit Zone

From a legislative perspective, immovable property has been treated differently from other business inputs because:

- It results in the creation of a capital asset of enduring nature, and

- GST is designed primarily as a tax on consumption, not on capital formation.

Accordingly, the restriction on ITC for construction of immovable property is not accidental or interpretational—it is a deliberate statutory exclusion. This approach is also aligned with the structure of the GST law, where plant and machinery are carved out as a specific exception, indicating that all other immovable property is intended to be excluded from ITC.

Position Before the Safari Retreats Judgment

Even before the Supreme Court’s ruling, courts and authorities generally acknowledged that Section 17(5)(c) and (d) impose a clear bar on ITC relating to immovable property. However, disputes arose in cases where:

- The constructed property was used for taxable outward supplies, such as leasing or renting; and

- Taxpayers argued that denial of ITC defeats the fundamental GST principle of seamless credit.

It was this tension between statutory restriction and business usage of immovable property that ultimately led to litigation culminating in the Safari Retreats decision.

What Was the Issue in Safari Retreats? (In Simple Terms)

The dispute in Safari Retreats did not arise because of ambiguity in the statutory text of Section 17(5). Instead, it arose from a practical business situation where the statutory restriction appeared to clash with the economic reality of a taxable business model.

Business Model Involved

The taxpayer constructed a commercial shopping mall, which was subsequently leased out to tenants. GST was charged on the rental income received from such leasing. The construction of the mall involved substantial inward supplies of goods and services on which GST was paid.

From a commercial perspective, the building was not used for personal or exempt purposes. It was an essential asset used exclusively for making taxable outward supplies in the form of renting of immovable property.

This fact pattern is common across India and is routinely encountered by:

- Commercial developers

- Mall owners

- Business groups leasing office or retail space

The case, therefore, carried significant industry-wide implications.

Why Input Tax Credit Was Claimed

The ITC claim was based on the following reasoning:

- Renting of commercial property is a taxable supply under GST;

- Construction of the mall was indispensable to that taxable supply; and

- Denial of ITC results in tax cascading, contrary to the fundamental GST objective.

The taxpayer did not dispute the existence of Section 17(5)(d). Instead, the argument focused on how the provision should be interpreted when construction is directly linked to taxable business income.

This distinction is important because the case was not about procedural non-compliance or misuse of credit, but about interpretational limits of a blocking provision.

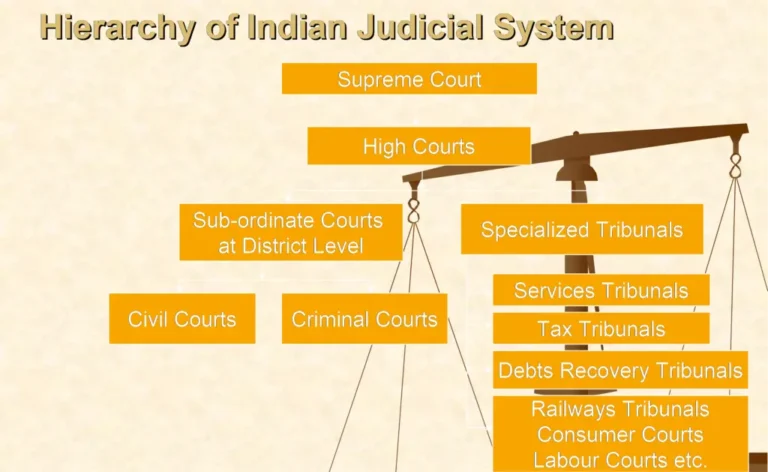

Core Legal Question Before the Courts

The central legal question before the courts was narrow and specific:

Whether input tax credit on construction of immovable property can be denied under Section 17(5)(d) even when such property is used entirely for making taxable outward supplies.

In other words, the issue was whether:

- The phrase “on his own account” should be interpreted broadly to cover all owned buildings, or

- It should be read narrowly to exclude situations where construction is integrally connected with taxable business activity.

Notably, the case did not involve:

- Personal use of property

- Exempt supplies

- Mixed-use scenarios

- Allegations of tax evasion

This made Safari Retreats a pure question of law, arising from a standard commercial fact pattern—one that GST professionals regularly advise on.

Supreme Court’s Ruling – What Exactly Did the Court Decide?

The Supreme Court’s judgment in Safari Retreats is often misunderstood as either expanding or completely shutting down the availability of ITC on immovable property. In reality, the Court did neither. Its ruling is best understood as a confirmation of legislative intent coupled with judicial restraint.

The Court’s Approach to Section 17(5)

At the outset, the Supreme Court recognised that Section 17(5) of the CGST Act is a conscious legislative restriction. The Court emphasised that GST, though based on the value-added principle, does not guarantee unrestricted availability of input tax credit in all circumstances.

The Court observed that:

- The right to input tax credit is a statutory right, not an inherent or constitutional right; and

- Parliament is competent to impose conditions and restrictions on such credit, including complete denial in specified cases.

Accordingly, the Court refused to read down or dilute Section 17(5)(c) and Section 17(5)(d) merely because the outward supply was taxable.

Why the Court Did Not Strike Down Section 17(5)

One of the key expectations from the litigation was that the Supreme Court might declare the blocking provisions unconstitutional or arbitrary. The Court, however, categorically declined to do so.

The reasoning was clear:

- The GST law itself expressly contemplates blocked credits;

- Section 17(5) begins with a non obstante clause, overriding Section 16; and

- Denial of ITC on immovable property serves a legitimate legislative purpose, namely exclusion of credit on capital assets other than plant and machinery.

The Court held that it is not for the judiciary to substitute its economic or tax policy preferences for those of the legislature, as long as the statutory provision is not manifestly arbitrary.

What Was Expressly Denied by the Supreme Court

Equally important is understanding what the Supreme Court explicitly rejected:

- The argument that ITC must be allowed merely because GST is paid on rental income;

- The contention that denial of ITC automatically defeats the GST objective of avoiding cascading; and

- The plea that commercial exploitation of an immovable property takes construction outside the scope of “own account”.

In effect, the Court made it clear that taxability of outward supply does not, by itself, override an express statutory bar on ITC.

Limited Scope Left Open by the Judgment

At the same time, the Supreme Court did not attempt to exhaustively define every possible factual situation. It confined its decision to the statutory framework and the facts before it, without laying down any general exemption for commercial buildings.

This careful approach indicates that:

- The Court upheld the rule, not exceptions; and

- Any scope for ITC must arise strictly from the language of the statute, not from broad GST principles.

What Survives After Safari Retreats – Situations Where ITC May Still Be Examined

After the Supreme Court’s ruling in Safari Retreats, it is clear that ITC on construction of immovable property is not freely available under GST. However, it would be equally incorrect to say that the judgment leaves no interpretational space at all. What survives is limited, fact-specific, and tightly controlled by the statutory language.

Distinction Between “Own Use” and “Furtherance of Business”

Section 17(5)(d) denies ITC on goods or services used for construction of immovable property on the registered person’s own account, even if such property is used in the course or furtherance of business.

The Supreme Court’s reasoning reinforces that:

- Ownership and capitalisation of the property are critical indicators; and

- Mere commercial use of a building does not take it outside the expression “on own account”.

In other words, using a building for business is not the same as constructing it for further supply. Where the construction results in an asset owned and capitalised by the taxpayer, the restriction under Section 17(5)(d) ordinarily applies.

Why the Door Is Not Fully Shut, but Heavily Restricted

The judgment does not declare that ITC on immovable property can never be examined. Instead, it clarifies that any such examination must arise strictly from:

- The language of the statute, and

- The factual character of the transaction, not from general GST principles.

Situations where construction itself constitutes a taxable outward supply, such as works contract services supplied further, are already carved out under Section 17(5)(c). Beyond such statutory exceptions, Safari Retreats does not create any new category of eligibility.

Accordingly, post-judgment, the scope for ITC survives only where a taxpayer can clearly demonstrate that:

- The construction is not on own account, and

- The inward supplies are directly linked to a taxable supply of construction or works contract services.

This is a narrow window, not a planning opportunity.

Importance of the Factual Matrix

The Supreme Court’s decision makes one aspect unmistakably clear:

ITC eligibility in immovable property cases is fact-driven, not assumption-driven.

Factors that assume significance include:

- How the property is reflected in the books of account

- Whether the expenditure is capitalised

- The nature of outward supplies linked to the construction

- The contractual and commercial structure of the transaction

In the absence of clearly distinguishable facts, tax authorities are justified in applying the statutory bar under Section 17(5).

From a professional standpoint, this means that generic arguments based on business use or revenue generation are no longer sufficient after Safari Retreats.

Practical Impact on Businesses and Professionals

The Supreme Court’s decision in Safari Retreats has significantly narrowed the scope for claiming ITC on construction of immovable property under GST. What was earlier argued on principle has now become largely settled on statute.

Developers and Commercial Lessors

For developers, mall owners, and commercial lessors, the judgment makes it clear that:

- Construction of buildings resulting in ownership and capitalisation is ordinarily treated as construction on own account; and

- The fact that rental income is taxable under GST does not override the restriction under Section 17(5)(d).

Accordingly, ITC claims on construction of commercial complexes, malls, and office buildings used for leasing carry a high litigation risk after Safari Retreats.

Corporates Constructing Own Premises

For corporates constructing head offices, factories, warehouses, or other captive premises, the position is now largely beyond doubt. ITC on such construction is clearly blocked, even where the premises are used exclusively for taxable business operations.

Professional Perspective

From an advisory standpoint, the judgment shifts the focus from interpretational arguments to factual evaluation and compliance certainty. Post Safari Retreats, aggressive ITC positions on immovable property are difficult to sustain unless the facts clearly fall outside Section 17(5).

Key Takeaways for GST Compliance Going Forward

- Section 17(5)(c) and (d) remain fully operative after the Supreme Court’s ruling.

- ITC on construction of immovable property is a statutory exclusion, not a procedural lapse.

- Taxability of outward supplies, such as rental income, does not automatically entitle ITC on construction costs.

- Any scope for ITC post Safari Retreats is narrow, fact-specific, and strictly statute-driven.

- Businesses should adopt a conservative compliance approach, supported by proper documentation and realistic risk assessment.

- Litigation should be pursued only where facts are genuinely distinguishable, not merely arguable.

You May Also Like

Sources

- The Central Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017, particularly Sections 16 and 17(5)(c) & (d)

- Explanation to Section 17(5) of the CGST Act (as enacted and amended)

- Judgment of the Supreme Court of India in Safari Retreats Pvt. Ltd. v. Chief Commissioner of CGST

Disclaimer

This article is published for educational and informational purposes only. It is intended to provide a general understanding of the law relating to ITC on immovable property under GST based on statutory provisions and judicial interpretation as on the date of publication.

It does not constitute legal, tax, or professional advice. Readers are advised to evaluate facts of their specific case and consult a qualified professional before taking any action or position under GST law.